Growing up, I used to look forward to the weekends. We had taught our family dog, Harry, to retrieve the Sunday newspaper from the end of our driveway. Understandably, this was an exciting event for a child. What followed was a ceremony that was often repeated: dog brings paper inside, dad unwraps it and reads it slowly while standing at the kitchen counter and drinking cups of black coffee. As I got older, I participated in the tradition.

My parents always joked about our local paper, and how seemingly minuscule events would make the front page (“Cow Gets Loose, Causes Traffic on Local Roads”). But despite this, it was an important source of information about our community that we turned to each day. I still have clippings of the scores of all of my high school tennis matches in a box somewhere, and I remember declaring the first time they were published that I had “made it into the newspaper!” It felt significant.

In the years that followed for our local paper, fewer of those charming, “local” stories made the front page, replaced by syndicated content coming from places like the AP. Gradually, almost everything about the community in which we lived disappeared from the pages, and our neighbors stopped subscribing.

Present day

Today, only about 14% of us pay for local news in some form, and U.S. newspaper circulation has reached the lowest levels ever recorded. Local newspapers haven’t just been phased out of homes, either. In late September, Kroger Co. announced that they would remove free weekly publications from all of their grocery stores, nationwide, sparking a “Don’t Lose Local News” advocacy campaign. This hit a number of alternative weeklies hardest, who scrambled to find new locations to distribute their papers. The response issued from a Kroger corporate affairs manager was that “more publications continue to shift to digital formats.”

This isn’t a unique story, and it’s one that’s been covered extensively. A 2018 report on “news deserts” by the University of North Carolina found that 1,800 local newspapers had folded since 2004, including 500 in more rural areas. It also discussed the rise of the “ghost newspaper,” one in which “routine government meetings are not covered, for example, leaving citizens with little information about proposed tax hikes, local candidates for office or important policy issues that must be decided.”

When we turn away from actual newspapers and toward the internet, we find that people do not pay for online news in the same way they paid for a printed paper to be delivered to their driveways or doorsteps. To supplement the lack of revenue for an industry that was already strapped, news outlets have necessarily implemented paywalls or made space for advertisements on their sites. Still, the growth in ad revenue has not been enough in many cases: local news sites have almost all had deep financial struggles, have been bought by larger conglomerates, or have had to cut their staff.

What does all of that look like in practice?

It looks like this:

And it looks like this:

I think this tweet says it best:

Without local news, I can’t do my job

Apart from my personal connections to the ritual of reading a newspaper, you might wonder why this matters to me. I work on our Cicero product, a database of elected officials and legislative districts. Cicero’s data powers applications that hope to inform the public (through a variety of different sources that touch thousands of people) about who their elected representatives are and how they can be contacted. Around election time, it is the task of my team to enter election results in every district in the nearly 1,000 chambers of government we maintain. As you can imagine, finding out who won a close race or a runoff election at the Federal level is relatively easy. Multiple news sources (some even without paywalls!) cover that information. At the state level, in most places these days, the secretary of state has a comprehensive website that lists results and is generally up to date.

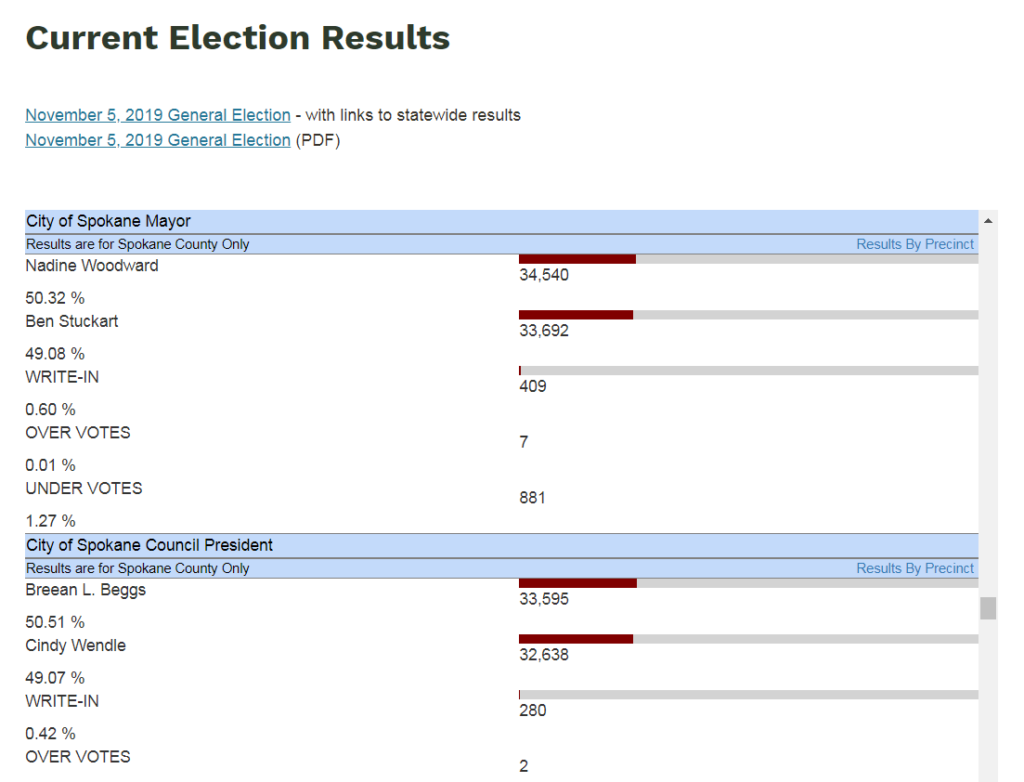

The tricky part comes at the local level, where arguably, knowing your representatives is most important and impactful. Combing through county board of elections sites sometimes only gets us so far. Take this example of the City of Spokane election results that were last updated on the night of an election and show races to have been decided by only a few votes.

What happens next? Some places automatically go to a runoff election, but others depend on a candidate requesting a recount. Some elections are not called until the final canvass of votes has been returned, but when will that be? Knowing this information is crucial to us being able to enter the correct person into office, and in a large number of these cases, we have to rely on someone writing about it in a medium that we can trust to be accurate and nonpartisan for the answer. For example, in the case of the Spokane, WA Council President, we needed to rely on this article to find out that one of the candidates had conceded. We can deal with the ads and autoplaying videos, when necessary. What we cannot deal with is when the story is just not covered.

This matters to me and to my team because we need this information to do our jobs. But for individuals, knowing who your elected representatives are is crucial to a functioning democracy. If not for local news, where will you find this information? In the moments after elections, or after a local city or town councilor steps down, when no information has been published online and no local newspaper is covering the story, in these moments our democracy is at stake.

Is there light at the end of the tunnel?

Local news sources have been crying out for a long time now, and there are many people who have been working to reverse the current trend. Two notable efforts that are close to our home:

- The Sample News Group is a Pennsylvania-based company that helps sustain small-town papers (like The Daily Herald; paid circulation: 1,700) by focusing on “micro-news.”

- The Knight Foundation, which has done extensive work in this area, together with the Lenfest Institute for Journalism awarded more than 5 million dollars in grants to three organizations in Philadelphia. The grant money is meant to help newsrooms use technology to cover their communities, better reach their audiences, and generate revenue.

Projects like these are inspiring, but they might not be enough. There is still a massive disconnect between how much Americans value their local news, and how much they are willing to pay for it. From our perspective, if this problem isn’t solved, it will largely impact the work we’re trying to do, and the people and organizations our services support. We hope to expand Cicero to cover a larger percentage of the more than 500,000 current elected officials in the United States, but without news on things like local election results, appointments, and officials stepping down mid-term, we can’t hope to provide accurate data.

The answers about the right programs and funding models to support the struggling news industry are perhaps still yet to be discovered. In the meantime, it’s been proven that as local journalism declines, so does government transparency and civic engagement. Information about local officeholders in the United States is already scarce, and as the news divide deepens, so too will gaps in awareness about local representation. So too will our collective participation in democracy.